In 701 B.C. the Assyrian empire was in its ascendancy. It had already vanquished the kingdom of Israel to the north including the capital at Samaria. It then prepared an assault on Judah and its capital at Jerusalem.

But in one of those significant events that changes the course of world history, Assyria was repelled. Jerusalem was saved until 586 B.C. when the Babylonians sacked the city, forcing its leadership class into exile.

Henry Aubin, in a major feat of scholarship, determines that Jerusalem was aided by a Kushite army from Africa which had marched northeast from the Nile valley. While the Bible attributes the Assyrian retreat to an angel and secular commentators cite pestilence, Aubin, in a meticulously documented work, demonstrates that an alliance with the African nation of Kush bolstered Jerusalem’s defences.

Kush, also known as Nubia, was located in what is now southern Egypt and northern Sudan. A monarchy that existed for more than 1000 years, from 900 B.C. to A.D. 350, Kushites held sway over Egypt from 712 B.C. to about 660 B.C. Of Egypt’s 31 dynasties, this, the 25th Dynasty, is the only one that all scholars agree, was black.

The commander of the Kushite expeditionary force was Taharqa (or as the Bible calls him Tirhakah). This Kushite prince, who had his own interests in halting Assyrian expansion, likely caught the aggressors by surprise as they prepared their siege of Jerusalem.

Aubin offers a thrilling military history and a stirring political analysis of the ancient world. He also sees the event as influential over the centuries.

The Kushite rescue of the Hebrew kingdom of Judah enabled the fragile, war-ravaged state to endure, to nurse itself back to economic and demographic health, and allowed the Hebrew religion, Yahwism, to evolve within the next several centuries into Judaism. Thus emerged the monotheistic trunk supporting Christianity and Islam.

Citation by Cynthia Good, Engel’s Long Time Editor

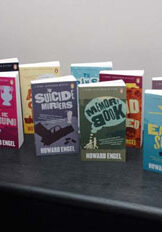

In the year that Howard Engel’s first novel The Suicide Murders was published, mysteries appeared featuring such well known PIs as Mike Hammer, Lew Archer, Travis McGee and Spenser. How daring to introduce a Benny Cooperman to that list!

With Benny, Howard proved that a “Yiddishe Kopf “can overcome the bad guys without guns or violence. By doing so he’s developed the ‘soft-boiled’ genre of mysteries, twelve Cooperman novels over thirty years, published in Canada, the US and in translation around the world. Benny does share traits with his hard boiled counterparts: he’s a loner, has his own sense of right and wrong, which can be a bit outside the law but he is always in pursuit of true justice; and he approaches his cases with dogged determination. But in a Cooperman mystery you’ll find references to his family, (his father’s clothing store, his brother who delighted his parents by becoming a doctor), his love of chopped egg sandwiches, his university prof girlfriend, all contribute to a uniquely Jewish approach.

At about the same time as The Suicide Murders was being published in 1980 in Canada, Margaret Atwood was working on Bodily Harm, Robertson Davies on Rebel Angels and Timothy Findley on Famous Last Words. Great novels, but pretty heavy stuff. Another gift that Howard gave us was humour, and what else would we expect from a good Jewish writer? And Benny is particularly Canadian Jewish. The Grantham setting based on St Catharines, a town, rather than the grit of the city, but not a cosy country English mystery either (Benny hates the country) and the gentler approach to crime solving, gives the Canadian flavor. Benny also befriends people from all walks of life – street people, librarians, cops – who are willing to help him out. And, again, as we’d expect from a Canadian writer, a cast of characters from all ethnic and national backgrounds.

No crime fiction novel had ever been set in Canada with a Canadian hero before Howard did it. When Engel found an audience for his writing, the floodgates opened for Canadian crime fiction. “Howard opened the door for probably 200 writers to come after him,” says Globe and Mail columnist Margaret Cannon. Last year alone, 43 crime fiction novels were published in Canada. After the first book, Benny Cooperman became almost a household word, a loveable character in the Canadian canon. He’s funny, sharp, endlessly curious, kind and full of arcane knowledge – just like his creator.

And here’s where I come in personally: I began working with Howard in 1983 when I acquired Murder Sees the Light for Penguin Books. I had just been hired to begin our Canadian publishing program and starting with Benny Cooperman seemed perfect – I loved mysteries, and to be part of the burgeoning crime genre in Canada delighted and challenged me. Howard and I worked together for another nine books, the most books I ever edited with an individual writer, and it was a wonderfully creative relationship. He was always receptive to ideas, easy going, and fun. I’ll lift up the veil behind the editorial process. What were the most common issues we dealt with in our editorial discussions? So many of his books just had too many characters, attesting to his capacious imagination and love of people. And sometimes his plots were too complicated, because his brain just works that way. He has a sweeping curiosity about everything and his store of knowledge informs his books and also makes him a wonderful lunch or dinner companion.

In 2000, Howard suffered a stroke which left him with alexia sine agraphia (he could write, but could not read). Despite this disability, he has gone on to publish several books, including his most recent Cooperman title East of Suez, a memoir (The Man Who Forgot How to Read) and one of his best Cooperman titles Memory Book (which he wrote during his recovery and I edited, and saw how his disability worked first hand). I’m sure he had moments of depression, but all we saw (the small team who worked with him after the stroke) was dogged determination, a sense of humour, a fascination with what was happening to him and a remarkable curiosity about his medical case and others like him. Just like his fictional character – and just like he had always been. And he never stopped writing for a moment.

Howard Engel has been honoured with the Arthur Ellis Award for Crime Fiction, the Derrick Murdoch Award, the prestigious Matt Cohen award for literature ((he was the first crime writer to receive it), an honorary degree, and the Order of Canada. His novels have been adapted for film (memorably starring Saul Rubinek as Benny) and radio and translated into more than a dozen languages.

Philip Marchand, then at the Toronto Star, wrote:

“Benny Cooperman is a character who somewhere in the collective literary unconscious of this country was crying to be invented. Canada needed its own private eye.†And I would add, so did its Jewish population.

On behalf of the jury of the Canadian Jewish Book Awards I am delighted to confer the Lifetime Achievement Award to Howard Engel, in recognition of his unique contribution to Canadian writing and to his creation of Benny Cooperman, one of this country’s best loved fictional characters. Engel’s creation of a Jewish detective has enriched the mystery genre and promoted a positive, alternative depiction of the private eye.

-30-

copyright Cynthia Good 2010